The Hodgson Clan

Where all things Hodgson come together...

The Border Reivers and their Emigration to America

The Border Clans

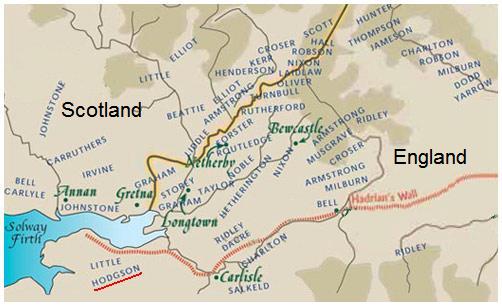

England and Scotland became one kingdom in 1603. In 1707 the Scots lost their national parliament, henceforth to be ruled from Westminster. For centuries beforehand, the remote Anglo-Scottish borderland region had been the lair of unruly clans and gangs of robbers that were largely beyond the reach of the law. A peculiar form of clan organisation grew up in this area. It existed from the Viking period (see the discussion of Atkinsons and Armstrongs elsewhere on this website) and was enhanced during the many Anglo-Scottish conflicts from the eleventh to the eighteenth century. This was the land of the ‘border reivers’.

The Hodgsons in Cumberland were themselves a clan organisation on the English side of the border (Fraser 1971). The history of the border clans is one of violence and eventual subjection by state authorities. Many were forced or obliged to emigrate to North America in the eighteenth century (Fischer 1989).

These clans recognised no legal authority other than the clan itself. Disputes led to blood feuds, sometimes lasting for generations. The very term ‘blackmail’ owes its origin to this region, involving the payment of protection money to powerful families.

These clans took advantage of their borderland location. They would steal goods, cattle and women from across the nominal border. Many took refuge in the ‘debateable lands’ where the border was ill-defined for centuries and no national legal authority held sway.

Anglo-Scottish Border Clans (including Hodgson)

Clan Organisation and Culture

The family was an extended unit, where first and second cousins bonded together in solidarity and kinship. The ‘derbfine’ meant all related kin within four generations. By tradition the derbfine was recognised as a basis for the inheritance of property.

Several derbfines were united in the clan proper. They ‘lived near to one another, were conscious of a common identity, carried the same surname, claimed descent from common ancestors and banded together when danger threatened’ (Fischer 1989, p. 663). Members of the clan shared a common identity and reputation. If one breached honour or trust, then it was to their common shame. If a woman were seduced or violated outside marriage, then all in her clan shared the humiliation. An attack from outside wrought vengeance from all.

Leadership of the clan was conferred by election. Candidates were confined to the derbfine. Disputing claims were sometimes settled by violence. Losers were at best humiliated and despised. The winner was honoured by deference and deep respect.

Marriages were traditionally the result of abduction. If the husband took his bride from a rival clan, then a ‘body price’ or ‘honour price’ might be necessary to stop a clan feud, even if the wife went voluntarily.

The man was the head of the immediate household. But men and women would share the heavy manual labour. Men would take responsibility as clan warriors.

It was traditional to name eldest sons with the first names of their grandfathers, and second or third sons after fathers. A secondary tradition was to give a son, as a first or middle name, the maiden surname of his mother or grandmother. The eldest daughter often took the first name of a grandmother.

Suppression and Emigration

Many unsuccessful attempts were made to suppress the lawless borderland clans. Finally, after the parliamentary union of England and Scotland in 1707, they were brutally crushed by the authorities. As the historian David Hackett Fischer (1989, pp. 629-30) puts it:

The pacification of this bloody region required the disruption of a culture that had been a millennium in the making. Gallows were erected throughout the English border counties, and put busily to work. Thrifty Scots saved the expense of a rope by drowning their reivers instead of hanging them, sometimes ten or twenty at a time. Entire families were outlawed en masse, and some were extirpated by punitive expeditions.

Some of these exiled clans took their memories and their culture with them to America. A wave of these migrants passed through Pennsylvania and into the Appalachians in the eighteenth century. Places in the USA were given imported names such as Durham and Westmoreland County. The most common British county name in Appalachia is Cumberland. There is a Cumberland town in Maryland, the Cumberland Mountains arise in Kentucky and there is Cumberland Knob in North Carolina. Many of these migrants took their wagons through the Cumberland Gap in search of a land and living further to the west. Some migrated to southern states such as Texas.

Influence on American Culture

David Hackett Fischer shows in his wonderful book Albion’s Seed (from which much of the information on this web page is taken) that borderland culture was transmitted through migration to the Appalachians and beyond, to states such as Oklahoma, Arkansas and Texas. In particular, the tradition of bridal abduction was exported to parts of America and survived for several generations. Borderland culture has shaped many remaining practices, including ‘country and western’ music and dress, and helps to account today for higher rates of violence in Texas and elsewhere. There is also systematic evidence that a ‘culture of honor’ survives in southern states (Nisbett and Cohen 1996), which would have partially been inherited from the borderlands of England and Scotland.

Not only surnames and DNA get transmitted; culture too crossed the Atlantic with American pioneers.

The First Hodgsons in North America

Information on the earliest Hodgsons to emigrate to North America (USA + Canada) will be gratefully received and presented on this website. 1850 data on the distribution of North American surnames show that Hodgsons were much more numerous in Illinois (seemingly about 1000 Hodgsons out of a total state population of about 851,000) than other states. By 1880 there was an additional Hodgson cluster in Minnesota.

Further Reading on other border clans:

Further reading on the Reiver clans Scott, Hunter, Burns, Thompson, Carre (Karre), Wilson, Bell, Dixon, Lowray, Gibson, and Turner can be found in My Unruly Clans by Andrew Comber.

Bibliography

Fischer, David Hackett (1989) Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press).

Fraser, George MacDonald (1971) The Steel Bonnets: The Story of the Anglo-Scottish Reivers (London: Barrie and Jenkins).

Nisbett, Richard E. and Cohen, Dov (1996) Culture of Honor: The Psychology of Violence in the South (Boulder CO: Westview Press).